beaulieu, derek. Seen of the Crime: Essays on Conceptual Writing. Montreal: Snare Books. 2011

“Please, no more poetry”: pleas from the scene of the crime, as poetry does its irreparable, imperfect damage. derek beaulieu, barely survivor of poetry, recounts some moments of close encounter. The preamble to the thirteen short essays, interviews, meanderings, that make up Seen of the Crime, are the confessions of a victim of poetry, or perhaps the warnings of a perpetrator. It sets a strident, polemic tone that is somewhat at odds with most of the pieces that follow. The pieces that follow being short, intimate, essays, interviews, close readings, portraits, of many things poetry. Included are, among others: confessions of bibliomania, an interview with Caroline Bergvall, and many close readings, for example of works by Craig Dworkin, Robert Fitterman, Kenneth Goldsmith, and bill bissett.

Clearly poetry, writing about poetry and publishing poetry are beaulieu’s passion and foremost activity. He also appears to be a ridiculously active community builder; or more precisely one should say communities, considering his prolific and activity as a writer (of several books and over 150 chapbooks), publisher of many exquisite limited-edition art/chapbooks, post-concrete poems, editor of UBUWeb’s new Visual Poetry section, and as a critic and reviewer. As an example that seems typical of the energy beaulieu puts into poetic communities (& also a statement that has inspired me ever since I read it) beaulieu states in an interview with fellow Canadian poet Sina Queryas:

I think it’s a poet’s responsibility to review books. As writers, we have committed ourselves to taking part in a dialogue, a discussion about art, and as such it’s our responsibility to review other books – to look at and write about other writers’ work – in order to further a discussion of the role of art.

Bealieu certainly accomplishes that and much more with this book. For all its elegant sleekness I have been enjoying, reading and returning to the Seen of the Crime for many weeks now. The book is definitely slim at under 70 pages, but the essays and ponderings it collects are fun, moving, evocative, provocative, and inspire to think again and hopefully anew. As proof of how much food for thought these short essays provide: what follows is a response to only one (the shortest) essay in the book.

Becoming found: Rob’s word shop

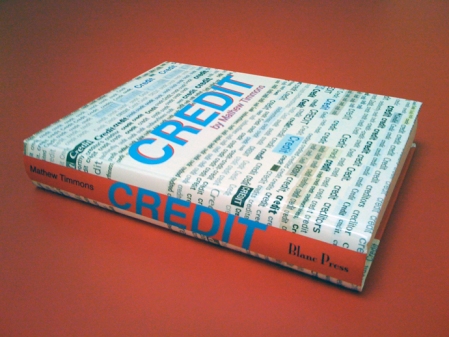

Fitterman would appear to simply be adhering to a basic tenet of capitalism: make something out of nothing; value out of debt. “Poetry decreases the value of the page it is written on” (was it Charles Bernstein who made that facetious comment?), so Fitterman is raising the value of poetry one could quip, or at least making it worth more than an empty page, simply by charging 1 Dollar per word. Matthew Timmons’ book Credit, parenthetically, is a purely conceptual example of the collapse into itself of this notion of value from zeros, credit from debt. Credit consists – in two parts, ‘Credit’ and ‘Debit’ – of all the credit card offers he received in a period of three weeks, as well as all the debit letters he receives over another two week period. Timmons cannot afford the 200-300 Dollar cost of purchasing Credit himself, nor (writes Vanessa Place) has he ever seen a hard copy of the thing.

But Fitterman, surely, as a self-proclaimed Conceptual poet – & therefore situated in a tradition of experimental poetry that precisely resists the capitalist commodification of language – is not trying to simply make money from other people’s words by exploiting the model of capitalist exchange? It is an intriguing situation; on one level what is taking place is a straightforward exchange of service and money. How much more commodified can a word get than being produced in response to a direct order and in exchange for a pre-determined price?

However, this is not an essentializing, metonymical kind of commodification that reduces letters or words to mere references for a chain store, or brand name (Golden Arches, VW). The words in Rob’s Word Shop do not refer to anything beyond themselves. Customers’ letters, words or sentences are produced not in the inhumane conditions, long, repetitive, back-breaking (or literally life-ending) hours of a sweat shop; instead, each order is tailor-made, with care for different specifications regarding the letter, word, sentence. Fitterman takes the time to decide with customers on the preferred font, length, size & much more.

Bartleby once more is on the same page as Fitterman here: Deleuze as well as Jacques Rancière argue in different ways that Bartleby’s statement “I would prefer not to” is not referential, but self-referential, referring only to his own desire to not act.

Jacques Rancière argues that this original should be linked to the eccentric – there is no mimesis, he does not imitate and cannot be imitated. Bartleby is inexplicable, he is from no where. [This echoes Deleuze appropriation of Samuel Butler’s ‘Erehwon’ as ‘a disguised no-where [and] a rearranged now-here’] Edward Willatt

Fitterman’s production of words on demand, can be thought of as coming from no-where, or a now-here in the very strict sense of being contingent on the desires of and the interaction with his customers. Their genesis is no longer the no-where of mass capitalist production, but the now-here of what is each time a new unexpected yet specific situation.

“Looking closely at words increases their materiality.” (James Sherry, The Language Book, 165) Rob and his customers take their time to pore over, ponder over, which word, how should it look, what materials should be used, can be used, where on the page, how big on the page, in what way on the page, & what shape should it take? Customer 37, on the last day, tries to find a way around the problem that there are not enough stencils to spell out her desired word ‘ampersand’:

One customer is not even sure how her own word – interpellation – is spelled & asks for a dictionary (which Rob does not have, but they work it out together):

Words become process here, a process of objectification, but not the kind that pins the words down and makes them do things that go against their inclination. Rather, words are objectified in the sense that they are studied and scrutinized as mysterious, ultimately unknowable objects in their own right. Queer in the sense of their uniqueness, eccentricity, monstrosity, being celebrated instead of overseen or put to some vicarious use in a marketing scheme, business plan, company logo; uncanny, by continually evading the subjugation of being completely known by some person pinning it down with a stare. “On errands of life these letters speed towards death” echoes beaulieu’s 9 Dollar commission to Rob’s Word Shop. In bringing people together & creating community, through the discussion of letters, the very letters speed towards the death of their ultimate unknowability, their ultimate evasiveness in the face of (an attempt at) being read.

Rob’s Word Shop, in which words are sold, paradoxically becomes here an inter-subjective, inter-personal exploration and an opening up to the singular and withdrawn qualities of those words, something that will remain unnamable even after the words have been stamped, sealed and delivered. What will be named, however, is the event(s) of these meetings, these convergences of word-person-person. “On one’s own solitude, one only holds a dialogue with oneself to stylize oneself…One does not write in order to say something, but to define a place where no one will be able to declare what hasn’t taken place.” (190) Steve McCaffery elegantly formulates a similar thought about the community-building effect of the removal from words, of the fetish of capitalization:

to demystify this fetish and reveal the human relationships involved within the labour process of language will involve the humanization of the linguistic Sign by means of a centering of language within itself; a structural reappraisal of the functional roles of author and reader, performer and performance; the general diminishment of reference in communication and the promotion of forms based upon object-presence: the pleasure of the graphic or phonic imprint, for instance, their value as sheer linguistic stimuli. Kicking out reference form the word (and from performance) is to kick its most treasured and defended contradiction: the logic of passage. (McCaffery, The Language Book, 189)

(A brief tangential footnote to a beautiful passage: why speak of “the humanization of the linguistic Sign” when we could speak of its de-humanization? Christian Bök – arguably the most in-human poet active – apparently believes that “poetry in the future will be written by machines for other machines to read” (Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing, 11). Be that as it may, or may not; I do certainly feel that it is much more interesting to include what is inhuman in us alongside all the humanizing. Not in spite of the ceaseless unimaginable inhuman atrocities we act out upon one another, but precisely because of them.)

Pingback: ‘Fidgeting with the seen of the crime’ « transversalinflections